“Kleptocracy” brings post-USSR Russia to life on stage

This play shown in Arena Stage D.C., portrays post-USSR Russia.

February 8, 2019

Russia: previously known for its communist state, the USSR; recently known for involvement in email scandals with the American government; currently in the D.C. theater scene in the form of a play.

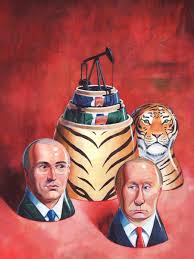

D.C’s Arena Stage’s “Kleptocracy” follows Mikhail Khodorkovsky (Max Woertendyke) in his rise into riches and the oil industry as a Russian oligarch, and his confrontation with young Vladimir Putin (Christopher Geary), who is also on the rise to power. “Kleptocracy”— meaning a government so corrupt that leaders use their power to exploit resources as to extend their personal wealth—is being performed Jan. 18 to Feb. 24, with ticket prices ranging from $41 to $95.

The play begins in the 1990s, when Khodorkovsky went from buying “loans for share” vouchers to acquiring Yukos Oil to the wealthiest man in Russia, and spans to 2010 when his prison sentence was extended.

During the time the play takes place, there was a multitude of events that impacted Khodorkovsky’s future as well as his relationship with Putin and, further, Russia’s relationship with the U.S.—specifically during a time where oil was currency in the diplomatic arena.

“Kleptocracy” starts off with a young Putin walking onto the stage reading a passage from the Russian story “How a Man Crumbled.” He then questions the audience of the meaning, assuming the role of a monologic narrator while simultaneously breaking the fourth wall. Though slightly confusing at first, the audience soon comes to the conclusion that aside from just being Putin, Geary’s character was meant to enlighten the audience regarding events happening in Russia at the same time as certain moments in the play.

Much of the first act was hard to decipher as it presented Khodorkovsky’s rise to power and featured multiple time jumps.

After Putin’s introduction to the play, a young Khodorkovsky enters the stage yelling “vouchers for cash”— referencing the Russian government’s privatization of state-owned assets through vouchers, which led to the rise in oligarchs like Khodorkovsky. In the scene, Khodorkovsky is pursuing his future wife Inna (Bronte England-Nelson) despite already being married with children.

Soon, the scene jumps to Khodorkovsky after he’s bought Yukos Oil, is married to Inna and has become the wealthiest man in Russia.

The rest of the scenes following seem to go by quickly due to the multitude of different scenes being featured. Conversations jump from Khodorkovsky and his partners to Putin and an unnamed female White House official (Candy Buckley) to Putin and Khodorkovsky, eventually ending the first act with Khodorkovsky’s arrest.

Even with the confusion of the first half, “Kleptocracy” manages to wrangle audience members into wanting to see the rest, with its adult humor and creative scene changes.

There are certain lines in the play not appropriate for younger audience members, though they do add an irreplaceable post-USSR Russia feeling.

The stage goes dark during set changes and projects 20th century Russian events onto the back wall, adding a mysterious allure that captures the full attention of audience members.

Though the scenes are all well-done—the acting, costumes and set—confusion amongst the audience continues to reign and leaves a slight disappointment prior to the second act.

The moment the second act begins, however, the audience knows it’s quite unlike the first half of the show as it’s where the main portion of the action takes place.

The second half focuses on Khodorkovsky’s time in jail and the proceedings that occurred during thay time, involving him and involving Putin and Russia’s relationship with the U.S.

With greater scene continuity and fewer time jumps, the second act seems to be more put together than the first. Though, in retrospect, the previous time jumps were necessary to get to the climax that is the second half.

Putin continues to be both himself and a narrator, using his moments alone on stage to expertly explain how and why everything is occurring.

Geary’s ability to simultaneously become a young Putin and an eccentric narrator do not go unnoticed by audience members. The aura of power that surrounded his character was hard to miss and something that made the show what it was. Without those scenes from him, coupled with Woertendyke’s development of Khodorkovsky’s character, “Kleptocracy” would be less drawing for the audience.

As the play continued on, audience members are brought to the edge of their seats.

Almost completely opposing to the first half, the second half brings the entirety of the show to life and entices viewers who gain a deep fascination for the inner workings of not only Russian politics, but the life of the people being depicted on stage, as well.

Along with greater action, the second half brings character development, as well as a development of the actors into the characters they portray.

By the time the play comes to a close, it would seem that the ending would be simple. On the contrary, the ending is so complex as to tempt viewers with a need to see more. The final note the play leaves on the audience is that of a cliffhanger—one that hints to viewers of future devious plans to come that could not even be imagined.

Without the second half, it’s hard to say that the play would be one to take the audience’s breath away and transport them into Russian political culture.

After the conclusion of “Kleptocracy,” it can be said with full certainty that this is a must-see play, especially for those interested in worldly politics and business, or just Russia in general.

Though it’s advised to have some knowledge of who Putin and Khodorkovsky are prior to seeing the show, a simple google search will do the trick and get you ready for an unforgettable experience.

If you’re confused at any time during the first half, know that you’re not alone but also that the best parts of the play are still yet to come.

“Kleptocracy” itself is a show that will blow you away by the last scene and show you that good things come to those who wait.