Throughout the last decade, the development of “true crime” as a form of entertainment has resulted in media from podcasts to novels to Emmy-winning television shows. However, this popularization comes with essential and nuanced ethical questions: are true crime shows inherently immoral because they treat the suffering of real human beings as entertainment? What responsibilities do the producer, consumer and distributor have regarding true crime’s effects on society?

When the primary purpose of true crime media is to entertain rather than inform, the industry profits on schadenfreude (pleasure derived from another person’s misfortune). The content of many true crime shows, from “Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” (2022) to “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile” (2019), relies on shock value and the stakes of reality to stimulate a viewer’s sympathetic nervous system. While there is a biological basis for our interest in these programs—the vigilance required from our ancestors to navigate dangerous environments—society’s specific fixation on true crime is a manifestation of a broader fascination with brutality and tragedy, like a car crash one cannot look away from. As a result, there is an experience of cognitive dissonance when we feel enjoyment from the relived trauma of others within the commodified true-crime media.

The factors of portrayal and perspective are also vital to the ethicality of true crime media. Objectively portraying a true crime case is ethical when fact-based, such as a documentary or a news broadcast. However, the producers and distributors should still have the consent of the victim (or their families if the victim is deceased) to release information to the public. Casting famous actors or actresses as the perpetrators can perpetuate the romanticization of heinous criminals. The show’s perspective plays a vital role in the audience’s takeaway of the crime. It is unethical to tell a true crime story from the point of view of the killer or the victim, as their accurate and exact thoughts, feelings and emotions are unknown; it is insensitive at best and misleading at worst. By intentionally misrepresenting the nature of the crime or putting words into the victim’s mouth, there is an inherent dramatization of the facts for entertainment purposes.

The ethicality of true crime stories in different mediums of off-screen art, such as fictional writing, visual art or music, depends on the artistic intent of the artist and the consent of the victim’s family. Specifically, if the artist is mining the victim’s trauma for non-political messages—whether through metaphor or allegory—then their art is morally tainted. This extends to attempts at storytelling or metaphor-making with the true crime case as the central focus. In essence, viewing tragedy as a source of artistic or aesthetic inspiration is a form of exploitation. However, it is important to distinguish between personal and political art. When the artist utilizes discretion and care with the tragedy in order to heal from or bring visibility to a particular socio-political condition, such as Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” or Peyton Scott Russell’s George Floyd mural, it transforms art-as-aesthetics into art-as-conversation.

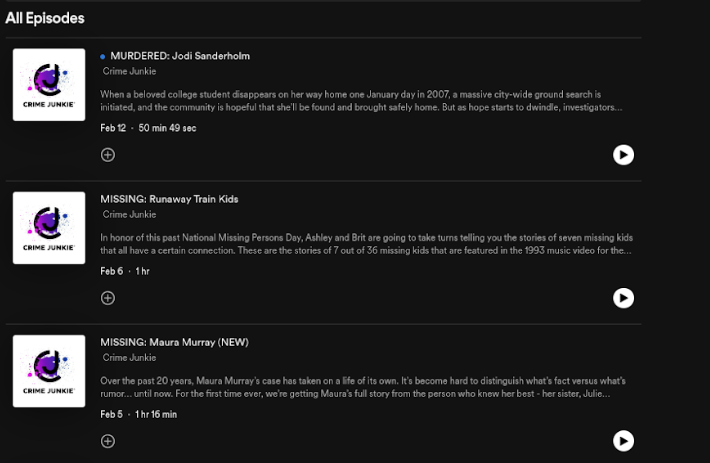

Finally, another facet that must be considered is the popularity of video essays and podcasts with true crime as their main topic, specifically, the portrayal of the subject and the monetization of the podcast. For example, putting on makeup or eating while discussing the case is extremely unethical because the creator is trivializing the trauma of the victim and their family. Their lives should not be minimized into a “storytime.” The pain that they endured should not be minimized into a palatable package, consumed by individuals from the safety of their bedrooms. Furthermore, the monetization of true crime is inherently suspicious: what is the goal of the people discussing the case? Suppose the creator publishes content with thorough research and ethical intent, such as spreading awareness or humanizing the victim’s life beyond death. In that case, they should not be deterred by a lack of monetary compensation because their goal is purely informational. Similarly, attempts at community-building on a foundation of true crime content are also morally dubious. When a creator holds exclusive content behind a paywall, such as Patreon, this violates the monetization clause and encourages parasocial relationships on the basis of a mutual enjoyment of true crime, which is objectionable and unsavory.

Overall, although the dramatization and fictionalization of true crime is unethical due to elements of exploitation and schadenfreude, an ethical approach to presenting true crime stories—whether through the form of television, art or podcasts—relies on the recency of the case, the perspective of which the story is told and the portrayal of the case.